Stubbornly naughty, properly defiant

When reflecting on Scud’s body of work, Christian Louboutin’s maxim “High heels are pleasure with pain,” comes to mind, as all his films are similarly permeated with the two. Audacious, passionate, cruel, loving, consistently stubborn and defiant by default, Scud strips down to his soul by stripping the most beautiful of men, letting them become naked and vulnerable, wandering between the realms of absolute pleasure, waking dreams and nightmares, in ponderment of the meaning and value of life, death and thereafter. These themes and explorations swirl across his oeuvre like the red thread of love and destiny.

When reflecting on Scud’s body of work, Christian Louboutin’s maxim “High heels are pleasure with pain,” comes to mind, as all his films are similarly permeated with the two. Audacious, passionate, cruel, loving, consistently stubborn and defiant by default, Scud strips down to his soul by stripping the most beautiful of men, letting them become naked and vulnerable, wandering between the realms of absolute pleasure, waking dreams and nightmares, in ponderment of the meaning and value of life, death and thereafter. These themes and explorations swirl across his oeuvre like the red thread of love and destiny.

Born in Guizhou in 1967, raised in Guangzhou and later Hong Kong as the Cultural Revolution gained momentum, Scud didn’t arrive at filmmaking straight away. It took travelling the world, a long enough stint in Australia, a solid career in IT and business and a realisation that it might have been time to stop living someone else’s dream life. He then moved back to Asia and founded the production company Artwalker.

With Naked Nations – Tribe Hong Kong (2024), the artist-provocateur now bids his farewell to filmmaking, leaving behind ten stand-alone films that form one singular relentless work of art. Deeply personal, visceral and aesthetically courageous as they are, Scud’s films ‘accidentally’ brought a new edge to Hong Kong queer cinema, the image of the Asian male body.

Artwalker’s first production, City Without Baseball (2007) co-directed by Scud and Lawrence Lau, opened Pandora’s box. Blurring the boundaries between fiction and documentary while playing with the iconographies of youth drama and sports films, the film fictionalised the lives of real-life Hong Kong baseball players, suggesting the male athletes might play homoerotic games or even be gay (a thought that even now makes headlines) and in the same gesture turning casually naked men into a symbol of defiance. While City Without Baseball might count as his directorial debut, for Scud, it is the film that followed that better marks his entrance on the stage: Permanent Residence (2008) is the first of his films deeply rooted in personal experience, biographically, mentally and emotionally.

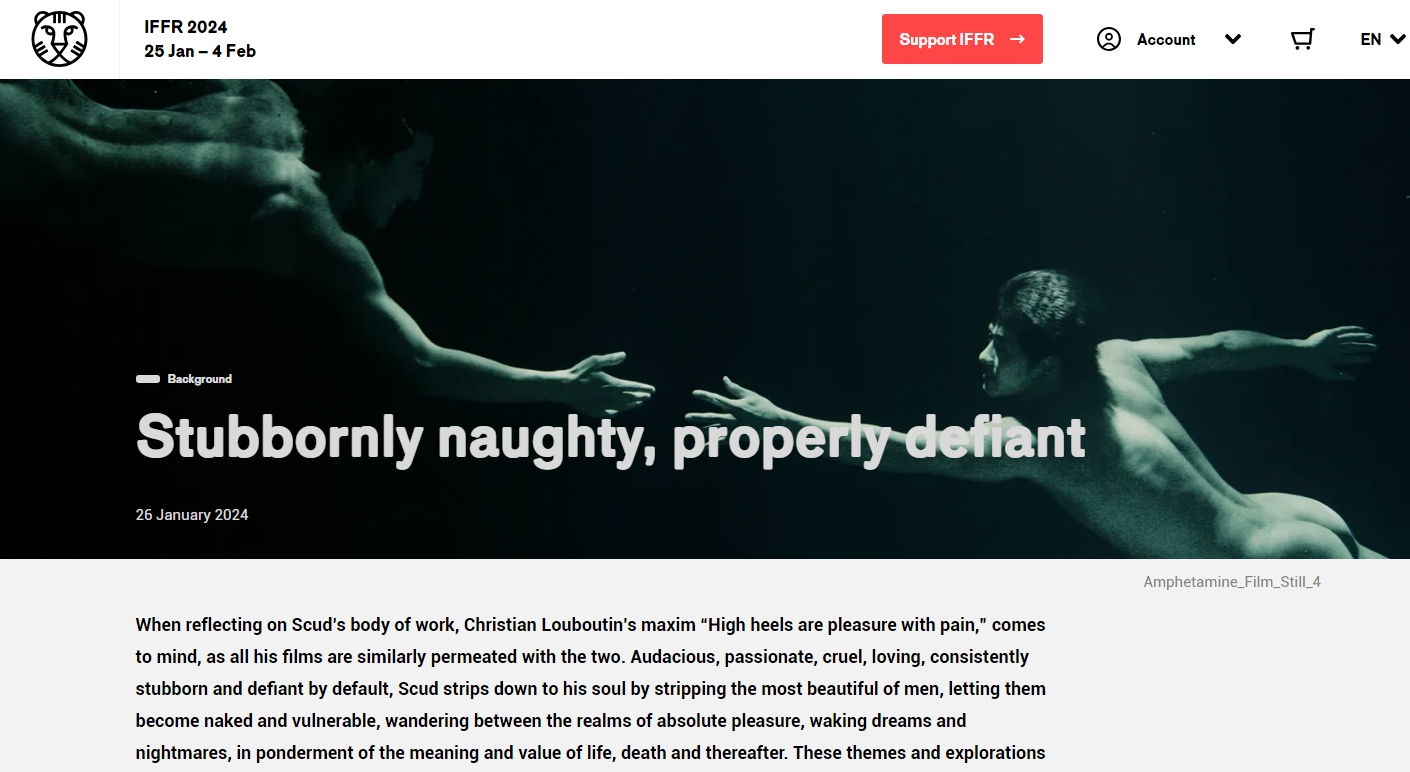

With the story of a handsome and brilliant IT guy who returns to the place he grew up, the place he might well presume ‘his’, Scud took the blueprints drafted in the previous film and laid solid foundations of a many-faceted world where fantasies become reality, but one that has no immunity from pain or heartbreak, or contemplations of life, love, death and belonging. It is also where the stream of reference between his films begins: by direct mention or re-appearance of the protagonist, but also specific locations. Among these locations, a boat holds a very special place. While slightly switching up roles, Amphetamine (2009) continues to explore the possibility of love between people who desperately need it, crave it, but only look for it in others – a love that only creates dependency and is deemed to let one down after a little game of use and abuse. Yet, it would take some time for them to realise that similarly to freedom, love is not and cannot be something that is observed as an outward fact; rather it must be something that is decided, moreover, without appeal – might it be done with volition? Hence, they become wanderers – teachers and disciples alike.

One of the many allures of Scud’s body of work lies in its challenging of norms while offering a blend of provocative storytelling and visual artistry that is as beautiful as it is shocking in its casual cruelty. For some, this expression might feel rather crude – people are not only ‘in nudes’, but naked, and pain and harm show on the physical level. Yet these are merely a stream of images fuelled by a very humanist intention. It is a peculiar perpetuum mobile: Scud’s experience energises his films and at the same time, filmmaking becomes his own life drive. Films seem to have become a safe place to learn about life, death, love – for others, for oneself and as such all these protagonists, for whom Scud cares deeply, and who carry at least a partial imprint, a projection, of himself.

This intensely personal approach makes them universal. It also allows the stories of others to seamlessly enter Scud’s storyworld and enrich it. That is the case in Love Actually… Sucks! (2010) and Voyage (2012). The first recounts six cases presented before a court where love unfolded terribly wrong, and the latter is an anthology on the ways of coping with the loss of a loved one based on Scud’s own experience and the experience of people he’s met. They are absurd, sardonic, perhaps cynical and surely filled with the will to understand deeply. After Utopians (2016) there can be no doubt of Pasolini’s impact on Scud; the images speak for themselves. In the meantime, the ideas have been part of the mix of inspirations which include the devastating narratives and sense of the absurd found in the works of John Maybury, Peter Greenaway and Pedro Almodóvar. The film also gives way to a sense of self-assertion as its protagonists embrace sex as an expression of life rather than proof of it, and the idea that home itself might be illusory, forever moveable and indistinct from oneself.

While watching the ten films in chronological order provides the satisfaction of witnessing a continuous evolution of the attitude to life and death, creation and (self)destruction, their recombination brings all sorts of different joys. One thing is definite though, that Naked Nations provides a closure for Scud as a filmmaker. But some more explorations through cinema precede this moment. Thirty Years of Adonis (2017) follows a young Beijing opera actor whose curiosity leads him to the world of male sex industries – a world full of power games and abuse, a landscape of sensuality, self-discovery and self-destruction to the point of self-surrender, ideas shared with Bodyshop (2022), which opens with suicide and leaves behind the horny ghost of a young man, traversing the globe, reminiscing on past lovers. While the treatment of their leads is harsh, both films exude eagerness for life and understanding thereof. They become death and afterlife observatories – as death is, after all, a part of life, and indeed Apostles (2022) becomes a reminder of how valuable being alive is.

Scud might not have found his home in Hong Kong, but he remains one of its most singular and naughty voices. Leaving filmmaking behind is as stubborn a decision as it was to begin with it. Yet, closing this chapter, a new intention is put into motion.

– Kristina Aschenbrennerova